Introduction

This post continues my notes on Smart UPS 750, three years later, when it was time to replace the batteries (because they barely held for 13 minutes). It should have been simple, but if I wrote this lengthy post about it, there was clearly something going on. I’ve also written a separate post on general insights on the theory behind lead-acid batteries.

Note that UPSes and their batteries is not my field. These are just my notes as I found my way through. Also, I’ve added to and modified this post several times, so there are definitely inconsistencies in my actions and conclusions, because I learned as I went.

So for short, the main takeaways are these:

- Update the time of last battery replacement with the UPS’ front panel interface (somewhere under Configuration). This makes the UPS realize there are new batteries inside, which changes the way it calculates the estimated runtime.

- Two standard 12V / 7AH lead acid batteries can be used instead of APC’s original battery pack. But check that the terminals are 6mm wide. There are mainly two kinds of terminals: F1 (4.75 mm wide) and F2 (6.35 mm wide).

- The “battery fill” percentage is close to meaningless.

- The displayed battery runtime is not reliable.

- Every now and then, yank the power cord and see how long the UPS lasts. Expect surprises both ways. Battery calibration doesn’t help much.

And now, the deep dive.

Replacing the batteries

The original replacement battery for this UPS is RBC48. But not only is this pack horribly expensive, it’s also hard to find in Israel (or maybe they’re not manufactured anymore?).

The process for battery replacement with non-APC batteries is shown in this video, but it’s really not complicated. Yank off the front panel, then the pull down the metal panel behind the former, and pull out the batteries gently. Use the harness that connects the two existing batteries on the new ones, push them in and you’re done. Plus some packing tape to keep the two batteries together.

However the original batteries’ contact terminals are about 6mm wide (F2), contrary to the ones on the battery I bought (F1), which were considerably smaller. So even though there was no problem connecting the batteries, it wasn’t all that reassuring that the contacts were smaller.

This is a picture taken from above, showing the original pair of batteries I pulled out from the UPS (click to enlarge):

The blue thing in the middle contains a fuse, and the black connector at the top mates with the UPS.

But when I powered up the UPS, the expected runtime shown on the display was just 13 minutes, even though the charge level appeared as 100%. I was surprised to see a 100% charge level on batteries that were just installed, and even more disappointed with the expected runtime. Could it be that bad? Both APC’s runtime chart and my own simple energy calculation (see below) pointed at one hour at least with the load I had. And it didn’t improve after letting the UPS work for a few hours.

My first though was that I had been sold exceptionally junky batteries. But I bought them at a reputable electronics shop, and they carried a timestamp indicating they were fresh (but see below, they were actually junk).

And then it occurred to me that I should tell the UPS that I had replaced batteries. So I went to the part in the UPS’ configuration menu for setting the month and year of the last battery change, and did that. And to my surprise, the runtime was adjusted to 1hr 12 minutes right away. There a few posts out there (this, for example) on how to “reset the battery constant” manually. It seems like this relates to the same thing.

Cute, I thought. But is that figure correct? So I let the UPS run on battery for a while. The estimated runtime went down in pace with the wall clock, but then suddenly, after 23 minutes, it took the power down.

So I reconnected the UPS back to power, and let the battery charge until it reached 100% again. At which point it reported:

$ apcaccess

APC : 001,027,0652

DATE : 2021-08-29 20:21:36 +0300

HOSTNAME : thehost

VERSION : 3.14.14 (31 May 2016) debian

UPSNAME : theups

CABLE : USB Cable

DRIVER : USB UPS Driver

UPSMODE : Stand Alone

STARTTIME: 2021-08-29 18:30:15 +0300

MODEL : Smart-UPS 750

STATUS : ONLINE

BCHARGE : 100.0 Percent

TIMELEFT : 23.0 Minutes

MBATTCHG : 5 Percent

MINTIMEL : 3 Minutes

MAXTIME : 300 Seconds

ALARMDEL : 30 Seconds

BATTV : 26.6 Volts

NUMXFERS : 0

TONBATT : 0 Seconds

CUMONBATT: 0 Seconds

XOFFBATT : N/A

STATFLAG : 0x05000008

MANDATE : 2018-05-22

SERIALNO : AS1821351109

NOMBATTV : 24.0 Volts

FIRMWARE : UPS 09.3 / ID=18

END APC : 2021-08-29 20:22:01 +0300

Smart UPS or what? If the battery died after 23 minutes last time, how much has it left when fully charged? Let me think… 23 minutes!

And yet, that sounds way too short for a new battery. More than 24 hours later, the same runtime estimation remained, going up and down a minute or so occasionally. So that’s that.

It could be correct, however. The way to find out is to try again after a month or so. For that, there’s battery calibration. Which for my UPS means “let the battery drain and measure its way down until it’s empty”. See my follow-up note on that: It’s more or less like unplugging power from the UPS, but less helpful it turns out. Note that the load is said to lose power at the end of this process, even though that didn’t happen to me. So the computer needs to be taken down safely, and then held in a state where a power failure won’t hurt (e.g. stuck in some boot menu). This way, it remains as an electrical load, but nothing bad happens when the power goes down.

Battery calibration is launched from the front panel menu as well. Why the best way to calibrate is to yank the power cord is explained in the follow-up note below.

Make sure the batteries are equally charged

Before connecting a pair of batteries in series (as in my case), it’s a good idea to charge them separately, if possible. That’s true in particular if a discharging test is made immediately after installation. Otherwise, differences in the charging levels may result in a deep discharge of one of the batteries. It’s the same principle as not mixing different batteries in any electronic device.

Alternatively, wait for a while (24 hours?) before the first attempt to discharge the batteries, so both batteries reach the same level by virtue of the floating current.

Otherwise, how can it go wrong? Say, for example, that the UPS stops discharging at 1.7V/cell, which is a rather conservative limit. This means 10.2V for a single battery. But if this is a pair of batteries, this means cutting off at 20.4V. If one battery is still before its steep downhill phase, it can be giving 12.0V. As a result, the other battery will go down to 8.4V when the discharging stops. That’s 1.4V/cell, which isn’t a good idea, except for with a high current discharge. In the datasheets, all discharge curves end at higher than 1.5V/cell, except possibly for with the higher currents.

A note on power consumption

It’s quite obvious that the computer’s power consumption depends on its activity. But as it turns out, the power consumption is higher before Linux’ kernel is loaded.

More specifically, when the computer is on the GRUB menu, the UPS reports 105W / 157VA. One could argue that this is as idle as the computer could be. But then, when Linux’ kernel has been loaded, and it prompts me for my disk unlock password, the power stands at 65W / 120VA. After Linux has booted completely and the desktop is up, it’s 70W / 127VA. So the Linux kernel surely does something to reduce the power consumption when it kicks off.

When compiling a Linux kernel with 12 processes, the power consumption goes to 165W, 217VA.

It’s quite evident that the power factor improves as the power consumption increases. This is in line with Corsair’s promise to attain power level of unity at full capacity (which is 850W, a long way to go).

I run all my battery tests with the computer on GRUB. One has to pick one scenario, and this one represents a computer under moderate load. Whatever that means.

Why a battery drain test is necessary

It’s not clear what my Smart 750 UPS did with the batteries when recharging after they were completely empty. Coulomb Counting is irrelevant on lead acid batteries, because they are constantly discharging. The battery is supplied with a “float current” while being fully charged to keep it in that state.

Besides, there are several factors that influence the battery’s discharging curve. It might discharge nicely for a while, and then suddenly the voltage drops abruptly because the lead plates are worn out. The only way to know about this is to reach that point.

Another factor is that even when the UPS reports that the battery is 100% full, it may still accumulate charge for a long while after that. The UPS might consider the battery full and provide it with a “floating current” but in reality it’s still charging the battery very slowly. A real discharge test should be made no sooner than 24-48 hours of charging.

Follow-up: Recalibrating the battery after two months

Being suspicious about the 23 minutes estimate, I took the computer down after running 76 days (on 14.11.21), kept it powered on so it would load the UPS, and ran a calibration test on the UPS. There’s nothing special about those two and a half months, it just happened to be a convenient time.

During those 76 days, I had monitored the UPS’ answer to apcaccess, and it was steady: The battery voltage remained between 26.8V and 27.0V, and the running time remained around 23 minutes. The UPS didn’t change its mind.

So about the calibration test itself: I started it from the front panel, under the Test Menu, and it read “CalibrationTest in Progress” (the missing space as on the screen). The UPS beeped just like when it’s on battery because of a power loss, and it hummed accordingly. After 20 minutes it went back to main power, claiming to have 15 minutes left. That’s it. It didn’t reach the stage of beeping rapidly, and neither did the power to the computer go off at any time.

At this point I yanked the main power cord, and let it run out. It kept going for another 5 minutes (despite the promise) and then beeped rapidly. 30 seconds later, power went off.

So all in all, it ran for 25 minutes before it died out. The 23 minutes estimate was quite accurate.

Conclusion: Don’t bother calibrating. Just yank the power cord, and measure time.

The third important takeaway is that those “Bull Power” batteries are more like bull-something-else, and I should schedule another battery replacement in a year or so.

And here comes the really funny part. After letting the UPS recharge fully, I checked it again:

$ apcaccess

APC : 001,027,0652

DATE : 2021-11-14 15:19:02 +0200

HOSTNAME : thehost

VERSION : 3.14.14 (31 May 2016) debian

UPSNAME : theups

CABLE : USB Cable

DRIVER : USB UPS Driver

UPSMODE : Stand Alone

STARTTIME: 2021-11-14 13:50:25 +0200

MODEL : Smart-UPS 750

STATUS : ONLINE

BCHARGE : 100.0 Percent

TIMELEFT : 34.0 Minutes

MBATTCHG : 5 Percent

MINTIMEL : 3 Minutes

MAXTIME : 300 Seconds

ALARMDEL : 30 Seconds

BATTV : 26.8 Volts

NUMXFERS : 0

TONBATT : 0 Seconds

CUMONBATT: 0 Seconds

XOFFBATT : N/A

STATFLAG : 0x05000008

MANDATE : 2018-05-22

SERIALNO : AS1821351109

NOMBATTV : 24.0 Volts

FIRMWARE : UPS 09.3 / ID=18

END APC : 2021-11-14 15:19:02 +0200

Is this a smart UPS or what? It just had a calibration cycle which ended with losing power after 25 minutes. How could it estimate 34 minutes now? Maybe if I try again I’ll get 34 minutes? And if this is because the PC consumes less power when Linux is running, why was it only 23 minutes before?

Don’t know. I’ve played with this enough.

Second replacement, 16.4.23

I wasn’t happy with those “bulls” batteries, so I went for an early replacement of these. It turns out that it’s quite difficult to find batteries that are anything but a complete no-name. I barely able to get my hands on a Ritar. And when I say barely, I mean that I managed to get batteries from Afik, which is an Israeli electronics shop (אפיק מ.ל.ה בע”מ in Hebrew). This shop pretends to have its own brand, with a battery labeled AK12-7. But I got a photo of a shipping bill, which indicated that the batteries are manufactured by Ritar. So I went for a pair of those. On the invoice I got from the shop, it says RT1270 (this is the datasheet).

According to the datasheet, the discharge time at 0.55C (see discussion about discharge rates in my separate post) should be one hour. My test ran at 105W, which is grossly 105W/24V =~ 4.4A, which is about 0.63C. So I should have expected 50 minutes or so.

These batteries have small (F1) contact terminals too. I didn’t even think about checking that before I ordered them, actually. But the datasheet says that the battery comes with both F1 and F2 terminals.

I’ll skip to the bottom line right away: These batteries were junk, much worse than the previous ones. It’s plain fraud to call these batteries RT1270. Or maybe it has to do with the timestamp on the battery, which says “201022″. What does it mean? Judging from another battery from the same manufacturer (but different model), which had the timestamp “221215″, the new battery in the UPS was manufactured in October 2020. That could explain things.

So to the story: First I tested the old batteries. I put the computer on the GRUB menu and yanked the power supply from the UPS. Actually, I aborted the first experiment and let the batteries refill on the first attempt. The reason was that the (Western Digital) hard disks made the noise of (proper) activity, so I guess they were doing some kind of self-maintenance or something. I suppose they should be able to take a power loss in the middle of whatever they were doing, but I didn’t want to push my luck. So I just waited long enough, and then they went silent again.

The UPS went down after 9 minutes. Its estimation prior to the test was 12 minutes. The estimation was not bad.

I replaced the batteries with the Afik (Ritar) pair (a.k.a. junk), updated the time of last battery replacement on the UPS, and turned it on. Something was apparently wrong. The UPS was connected to proper power supply, and yet the computer didn’t switch on properly: It powered on, and after a few seconds it had some kind of reboot. It wasn’t clear what the problem was. It could also be because of a problematic USB hub, which tends to irritate the computer (partly because it has its own power supply).

At a later stage I discovered that the BIOS had been reset. Maybe because the computer had been powered off for a relatively long time. How did I notice? Because the CPU fans made more noise than usual, and the CPU’s temperature was lower than usual. I’ve changed the settings in the BIOS to silence the fans somewhat (within safe limits, of course). Plus the RGB sequence of the LEDs inside the computer stopped working. Should I change the BIOS’ battery too?

What I did next was a bit random, but at some point the UPS requested me to confirm that the battery had been replaced.

I took out the battery and pushed it in again. Maybe a loose connection? Who knows. Eventually, I connected the UPS to power, turned on the computer, and all ran fine.

The UPS said that the battery’s charge was 100% and promised all kinds of battery times (mostly around 50 minutes).

I then ran a battery test again. It lasted 5 minutes. When the UPS went on again, it gave the battery 28% and promised 14 minutes. Not so smart UPS.

So I let the battery load to 100% again (that took about 90 minutes), and ran a second battery test.

Bottom line: The UPS promised 49 minutes, in reality it held 11 minutes. This promise made sense, as it was probably based upon 0.63C. No chance in the world that this is an RT1270. Not a decently fresh one, anyhow.

So the old batteries, which I considered new held held 23 minutes when they were new, and 9 minutes after roughly a year and a half. These new batteries held 11 minutes as new!

Restarting the UPS, it reported 0% battery (make sense, doesn’t it?) and no 0 minutes runtime. After getting fully charged, the UPS promised 17 minutes. But that was with Linux running, so the power consumption is lower than the test. So it’s a reasonable estimation for a horrible battery.

Conclusion: I need to replace the batteries again, within a year. The computer shuts itself down after 5 minutes, so I guess it will be fine, but this is ridicolous.

Strategy for the next time

After two fiascoes, I’m changing strategy. So these are things I’m going to insist on:

- The marking on the battery should belong to a company that has a more or less proper website, from which I can download a datasheet.

- The datasheet should include discharging characteristics, either in the form of curves or tables, preferably both.

- The battery’s model code, as it appears in the datasheet, should be printed on the battery.

- If the battery is marked with the name of an Israeli importer, it’s by far not as good, even if the importer publishes a datasheet that is possibly identical to the one of the manufacturer.

- The manufacturing date of the battery should be marked on the battery. It should be easy to figure out what it means, and the battery should be fresh of course.

- Prefer an F2 terminal

- Reputable brand is a bonus.

The rationale: A datasheet with discharging characteristics is a commitment. If a large company buys 1000 batteries, and tests a few samples just to find out that they don’t meet the specs, a hefty lawsuit may follow. No sane battery manufacturer will take that risk if it can’t ensure that their batteries perform well.

I couldn’t find such a datasheet for “Bulls Power”, and surely not for that Afik piece of junk. The latter was probably manufactured by Ritar, but not with their commitment.

Not going to insist on: A known brand. Ritar batteries are unavailable in Israel at the moment, an Yuasa’s batteries cost a fortune. Their datasheet shows discharging graphs, of course. But no tables.

But more than anything, it seems like it’s a matter of age. I don’t think anyone manufactures really bad batteries to begin with. I speculate that those junk brands buy old batteries from good manufacturers, and market them with a different name, at a low price.

Who to buy from

Obviously, web shops are the easiest options. If they cooperate with sending me photos of the battery (see below). If not, go for bricks and mortar electricity shops (Erco, for example). Also consider shops and repair shops for motored toy vehicles for small kids. The search word in Hebrew for that is ממונעים (which means “motored”) but is somehow a collective term for these toys.

Is this a Covid-19 thing?

I called up Lion Electronic‘s sales (a company I consider reputable) for a couple of Yuasa batteries (200 NIS each, April 2023), and I was told that they won’t sell me two batteries at that price, because they are imported specially, and that has an extra cost.

My next hope was to get an Aokly 6FM7/6FM9, which are quite available in Israel. However, as of April 2023, two different suppliers told me that it had no manufacturing date printed on it. Which is really weird. So this manufacturer is irrelevant.

I made other significant attempts to get a battery that meets the above criteria in May 2023, and failed: Every time I asked for a photo of the battery and its timestamp, I got no response, or a rather negative one. I got online purchase orders canceled twice while attempting to buy a CSB battery from AlPesek, which is an importer of this battery. After talking with someone at the company about manufacturing date, and putting that request in the comments of the order, the company canceled the order, claiming that they don’t work with end customers (so why was it listed on the website?) and the batteries were delisted from the website. Trying to get the same battery from a web shop (that is, from the same source, but indirectly), I got the order canceled again, with the supposed reason that the minimum purchase for resellers is 10 units.

And there were several other attempts that ended with the other side simply not cooperating with sending me a couple of photos.

At one of Erco‘s shops, I found a VisionNet battery, which is apparently a local brand made up by Telran (a respectful company). The interesting thing about this battery is that it said “Production date 06/2022″ on the battery itself, and the guy at the shop told me that it had arrived a week earlier (and I believe him, the boxes in the storage were new). Also, there are several photos of the battery with this model, but they look different, and none have that timestamp. So it appears like Telran shops around for batteries and put their own marking on them. And that leaves the question how a battery that arrived a week ago is a year old. So the production date is probably something that the real manufacturer promised. Can that be trusted? I don’t know. If there was any battery I thought seriously about trying, it’s a pair of these.

Given this rather odd picture, I speculate that there was a lot of batteries that got stuck in storage, somehow related to Covid-19. And now the manufacturers need to get rid of a whole lot of old, and hence damaged batteries. That’s the best explanation I have to all these batteries with no date marking, plus a lot of weird behavior.

My decision was hence to stop my attempts to replaced the batteries in my UPS for six months, and try again somewhere towards the end of 2023.

Third battery replacement, 17.12.23

I went into Erco‘s shop in Kiryat Ata, and was offered a couple of Vega Power NP12-7 batteries. Never heard about that brand? Neither have I. Neither did this company have a reassuring Internet footprint. But the batteries had an an engraved timestamp saying 10/08/2023 and they had F2 terminals. So I bought a couple of them, at a price of 120 NIS, VAT included. Cheap, in other words.

And the answer to my previous question: Yes, the lack of fresh batteries was most likely a Covid-19 thing.

I ran a detailed discharging test on these two batteries (as well as on the Afik batteries), which I write about in that separate post. Spoiler: The discharging test doesn’t say too much about how the batteries will behave inside the UPS.

First, I wanted to check the situation of the Afik batteries that were already inside the UPS. I brought down the computer to where GRUB waits for prompt, so the UPS reported power consumption was 105W / 150VA. At this point, the UPS promised 12 minutes.

So I yanked the power cord. The UPS began panic beeping after 7:30 minutes, stating 3 minutes were left, which dropped down to 0% and 0 minutes quite soon. Contrary to its pessimistic estimation, the UPS kept up the power for quite long after that, so the total time with power ended up at 22:00 minutes.

Say what? The same batteries held 11 minutes when I first put them in the UPS, and now the time doubled?!

If I don’t want to develop mysterious theories about what happens inside the battery, the explanation could be that the battery was far from being fully charged when I tested it a few months earlier: The UPS claimed that the battery was 100% full after 90 minutes, but it’s quite possible that this estimation was anything but accurate.

It’s also worth citing Power Sonic’s Technical manual: “By cycling the battery a few times or float charging it for a month or two, the highest level of capacity development is achieved. Power-Sonic batteries are fully charged before leaving the factory, but full capacity is realized only after the battery has been cycled a few times or been on float charge for some time”. This is written about another lead-acid battery of course, but maybe it’s a thing that a few months inside the UPS does the battery good.

I replaced the Afik batteries with Vega Power’s. These batteries had been separately charged with another UPS for 48 hours each. After updating the battery replacement date on the UPS (i.e. telling the UPS that there are new batteries inside), the UPS initially promised an uptime of above an hour, and then swayed along until it gradually stabilized at 49 minutes.

Yanked the power cord. All was good and calm until panic beeping started after 28:15 minutes, after which the power went out just a few seconds later. Boom.

The computer was stable on the GRUB menu throughout all this.

So what’s the verdict? I don’t know. The discharging tests that I ran on both pairs of batteries made things even more confusing: Vega Power performed really well, and Afik didn’t worse, but not much worse.

The only clear conclusion is that a UPS discharge test is required every now and then. There’s no way around this.

Repeated discharging test, 22.3.24

Three months later, I ran the same discharging test on the Vega Power batteries. The panic beep began after 22:10 minutes. At 31:30 minutes, the panic beep went off, and then it went on and off sporadically as the UPS’ estimation for remaining time fluctuated between 3 and 6 minutes. At 33:50 minutes the panic beep became steadily on again, and at 34:20 the UPS went off.

In short: Three months of floating current added 6 minutes to the battery time. And an even more confused ride as the battery discharged.

One more discharging test, 20.4.25

A bit more than a year later, yet another test on exactly the same battery. There had been no power interruptions inbetween, so this was the first time the battery discharged. So with the GRUB menu on, the UPS claimed its load as 105W and 150VA, promising 34 minutes. The UPS held power calmly for 22 minutes, with the promised remaining time decreasing from the original 34 minutes in pace with the time elapsed. But after 22 minutes, the panic beep went on, the promised time showed one minute, and it didn’t hold even that. Power off.

In summary: One year later, the battery had lower capacity, but still quite reasonable. The UPS itself, however, gambled on the last figure it had at hand.

Forth replacement, 28.6.25

I got two Yuasa NP7-12 from Batteriexperten as their price was lower than others with a clear margin (about $38 each). Small terminals (F1, unfortunately, but there were no F2 available anywhere near), both marked 24110435, probably meaning they were both ~8 months old, which is reasonable.

Measured voltage before connecting to anything (OVC at equilibrium), room temperature:12.857V on one battery, and 12.863V on the other. With a 6 mV difference, it’s safe to assume they are equally charged. So no need nor point pre-charging them separately. Being an AGM battery, this indicates a charge level somewhere between 90-100%, in line with what one would expect from a battery of this sort and age. In other words, it’s probably fresh and in good shape.

I put the batteries inside the UPS and let it run for 7 days so that they would be in good shape for the test. Which I ran on 6.7.25.

I went for the same GRUB menu scenario, however the UPS reported 120W / 157VA this time. This is higher than the other tests, because I ran the test with a different monitor, which eats more power. The promised run time was 44 minutes (a wild guess, once again, because the UPS didn’t know what’s installed).

When yanking the power cord, the UPS raised its power measurement to 135W / 202VA, and the time estimate immediately went down to 37 minutes.

After 29 minutes, the estimation was 13 minutes left. Panic beep at 33:30, power down at 34:10 (40 seconds later). That’s the best result so far, and not all that off the estimate after the power cord was yanked. So yay to Yuasa. Let’s see how they hold with time.

Introduction

Occasionally, I download / upload huge files, and it kills my internet connection for plain browsing. I don’t want to halt the download or suspend it, but merely calm it down a bit, temporarily, for doing other stuff. And then let it hog as much as it want again.

There are many ways to do this, and I went for firejail. I suggest reading this post of mine as well on this tool.

Firejail gives you a shell prompt, which runs inside a mini-container, like those cheap virtual hosting services. Then run wget or youtube-dl as you wish from that shell.

It has practically access to everything on the computer, but the network interface is controlled. Since firejail is based on cgroups, all processes and subprocesses are collectively subject to the network bandwidth limit.

Using firejail requires setting up a bridge network interface. This is a bit of container hocus-pocus, and is necessary to get control over the network data flow. But it’s simple, and it can be done once (until the next reboot, unless the bridge is configured permanently, something I don’t bother).

Setting up a bridge interface

Remember: Do this once, and just don’t remove the interface when done with it.

You might need to

# apt install bridge-utils

So first, set up a new bridge device (as root):

# brctl addbr hog0

and give it an IP address that doesn’t collide with anything else on the system. Otherwise, it really doesn’t matter which:

# ifconfig hog0 10.22.1.1/24

What’s going to happen is that there will be a network interface named eth0 inside the container, which will behave as if it was connected to a real Ethernet card named hog0 on the computer. Hence the container has access to everything that is covered by the routing table (by means of IP forwarding), and is also subject to the firewall rules. With my specific firewall setting, it prevents some access, but ppp0 isn’t blocked, so who cares.

To remove the bridge (no real reason to do it):

# brctl delbr hog0

Running the container

Launch a shell with firejail (I called it “nethog” in this example):

$ firejail --net=hog0 --noprofile --name=nethog

This starts a new shell, for which the bandwidth limit is applied. Run wget or whatever from here.

Note that despite the –noprofile flag, there are still some directories that are read-only and some are temporary as well. It’s done in a sensible way, though so odds are that it won’t cause any issues. Running “df” inside the container gives an idea on what is mounted how, and it’s scarier than the actual situation.

But be sure to check that the files that are downloaded are visible outside the container.

From another shell prompt, outside the container go something like (doesn’t require root):

$ firejail --bandwidth=nethog set hog0 800 75

Removing bandwith limit

Configuring interface eth0

Download speed 6400kbps

Upload speed 600kbps

cleaning limits

configuring tc ingress

configuring tc egress

To drop the bandwidth limit:

$ firejail --bandwidth=nethog clear hog0

And get the status (saying, among others, how many packets have been dropped):

$ firejail --bandwidth=nethog status

Notes:

- The “eth0″ mentioned in firejail’s output blob relates to the interface name inside the container. So the “real” eth0 remains untouched.

- Actual download speed is slightly slower.

- The existing group can be joined by new processes with firejail –join, as well as from firetools.

- Several containers may use the same bridge (hog0 in the example above), in which case each has its own independent bandwidth setting. Note that the commands configuring the bandwidth limits mention both the container’s name and the bridge.

Working with browsers

When starting a browser from within a container, pay attention to whether it really started a new process. Using firetools can help.

If Google Chrome says “Created new window in existing browser session”, it didn’t start a new process inside the container, in which case the window isn’t subject to bandwidth limitation.

So close all windows of Chrome before kicking off a new one. Alternatively, this can we worked around by starting the container with.

$ firejail --net=hog0 --noprofile --private --name=nethog

The –private flags creates, among others, a new volatile home directory, so Chrome doesn’t detect that it’s already running. Because I use some other disk mounts for the large partitions on my computer, it’s still possible to download stuff to them from within the container.

But extra care is required with this, and regardless, the new browser doesn’t remember passwords and such from the private container.

Using a different version of Google Chrome

This isn’t really related, and yet: What if I want to use a different version of Chrome momentarily, without upgrading? This can be done by downloading the .deb package, and extracting its files as shown on this post. Then copy the directory opt/google/chrome in the package’s “data” files to somewhere reachable by the jail (e.g. /bulk/transient/google-chrome-105.0/).

All that is left is to start a jail with the –private option as shown above (possibly without the –net flag, if throttling isn’t required) and go e.g.

$ /bulk/transient/google-chrome-105.0/chrome &

So the new browser can run while there are still windows of the old one open. The advantage and disadvantage of jailing is that there’s no access to the persistent data. So the new browser doesn’t remember passwords. This is also an advantage, because there’s a chance that the new version will mess up things for the old version.

This should have been a trivial task, but it turned out quite difficult. So these are my notes for the next time. Octave 4.2.2 under Linux Mint 19, using qt5ct plugin with GNU plot (or else I get blank plots).

So this is the small function I wrote for creating a plot and a thumbnail:

function []=toimg(fname, alt)

grid on;

saveas(gcf, sprintf('%s.png', fname), 'png');

print(gcf, sprintf('%s_thumb.png', fname), '-dpng', '-color', '-S280,210');

disp(sprintf('<a href="/media/%s.png" target="_blank"><img alt="%s" src="/media/%s_thumb.png" style="width: 280px; height: 210px;"></a>', fname, alt, fname));

The @alt argument becomes the image’s alternative text when shown on the web page.

The call to saveas() creates a 1200x900 image, and the print() call creates a 280x210 one (as specified directly). I take it that print() will create a 1200x900 without any specific argument for the size, but I left both methods, since this is how I ended up after struggling, and it’s better to have both possibilities shown.

To add some extra annoyment, toimg() always plots the current figure, which is typically the last figure plotted. Which is not necessarily the figure that has focus. As a matter of fact, even if the current figure is closed by clicking the upper-right X, it remains the current figure. Calling toimg() will make it reappear and get plotted. Which is really weird behavior.

The apparently only way around this is to use figure() to select the desired current figure before calling ioimg(), e.g.

>> figure(4);

The good news is that the figure numbers match those appearing on the windows’ titles. This also explains why the numbering doesn’t reset when closing all figure windows manually. To really clear all figures, go

>> close all hidden

Other oddities

- ginput() simply doesn’t work. The workaround is to double-click any point (with left button) and the coordinates of this point are copied into the clipboard. Paste it anywhere. Odd, but not all that bad.

- Zooming in with right-click and then left-click doesn’t affect axis(). As a result, saving the plot as an image is not affected by this zoom feature. Wonky workaround: Use the double-click trick above to obtain the coordinates of relevant corners, and use axis() to set them properly. Bonus: One gets the chance to adjust the figures for a sleek plot. If anyone knows how to save a plot as it’s shown by zooming, please comment below.

So I have written a function, showfile() for Octave 4.2.2 on Linux, which accepts a file name as its argument. And now I want to run it on all files in the current directory that match a certain pattern. How?

So first, obtain the list of files, and put it in a variable:

>> x=ls('myfiles*.dat');

This creates a matrix of chars, with each row containing the name of one file. The number of columns of this matrix is the length of longest file name, with the other rows padded with spaces (yes, ASCII 0x20).

So to call the function on all files:

>> for i=1:rows(x) ; showfile(strtrim(x(i,:))); end

The call to strtrim() removes the trailing spaces (those that were padded), so that the argument is the actual file name. If the real file name contains leading or trailing spaces, this won’t work (but who does that?). Spaces in the middle of the file name are OK, as strtrim() doesn’t touch them.

After a few days being happy with not getting spam, I started to suspect that something is completely wrong with receiving mail. As I’m using fetchmail to get mail from my own server running dovecot v2.2.13, I’m used to getting notifications when fetchmail is unhappy. But there was no such.

Checking up the server’s logs, there were tons of these messages:

dovecot: master: Warning: service(pop3-login): process_limit (100) reached, client connections are being dropped

Restarting dovecot got it back running properly again, and I got a flood of the mails that were pending on the server. This was exceptionally nasty, because mails stopped arriving silently.

So what was the problem? The clue is in these log messages, which occurred about a minute after the system’s boot (it’s a VPS virtual machine):

Jul 13 11:21:46 dovecot: master: Error: service(anvil): Initial status notification not received in 30 seconds, killing the process

Jul 13 11:21:46 dovecot: master: Error: service(log): Initial status notification not received in 30 seconds, killing the process

Jul 13 11:21:46 dovecot: master: Error: service(ssl-params): Initial status notification not received in 30 seconds, killing the process

Jul 13 11:21:46 dovecot: master: Error: service(log): child 1210 killed with signal 9

These three services are helper processes for dovecot, as can be seen in the output of systemctl status:

├─dovecot.service

│ ├─11690 /usr/sbin/dovecot -F

│ ├─11693 dovecot/anvil

│ ├─11694 dovecot/log

│ ├─26494 dovecot/config

│ ├─26495 dovecot/auth

│ └─26530 dovecot/auth -w

What seems to have happened is that these processes failed to launch properly within the 30 second timeout limit, and were therefore killed by dovecot. And then attempts to make pop3 connections seem to have got stuck, with the forked processes that are made for each connection remaining. Eventually, they reached the maximum of 100.

The reason this happened only now is probably that the hosting server had some technical failure and was brought down for maintenance. When it went up again, all VMs were booted at the same time, so they were all very slow in the beginning. Hence it took exceptionally long to kick off those helper processes. The 30 seconds timeout kicked in.

The solution? Restart dovecot once in 24 hours with a plain cronjob. Ugly, but works. In the worst case, mail will be delayed for 24 hours. This is a very rare event to begin with.

Introduction

Checking Xillybus’ bundle for Kintex Ultrascale+ on Vivado 2020.1, I got several critical warnings related to the PCIe block. As the bundle is intended to show how Xillybus’ IP core is used for simplifying communication with the host, these warnings aren’t directly related, and yet they’re unacceptable.

This bundle is designed to work with Vivado 2017.3 and later: It sets up the project by virtue of a Tcl script, which among others calls the upgrade_ip function for updating all IPs. Unfortunately, a bug in Vivado 2020.1 (and possibly other versions) causes the upgraded PCIe block to end up misconfigured.

This bug applies to Zynq Ultrascale+ as well, but curiously enough not with Virtex Ultrascale+. At least with my setting there was no problem.

The problem

Having upgraded an UltraScale+ Integrated Block (PCIE4) for PCI Express IP block from Vivado 2017.3 (or 2018.3) to Vivado 2020.1, I got several Critical Warnings. Three during synthesis:

[Vivado 12-4739] create_clock:No valid object(s) found for '-objects [get_pins -filter REF_PIN_NAME=~TXOUTCLK -of_objects [get_cells -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GT*E4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST}]]'. ["project/pcie_ip_block/source/ip_pcie4_uscale_plus_x0y0.xdc":127]

[Vivado 12-4739] get_clocks:No valid object(s) found for '--of_objects [get_pins -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GTYE4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST/TXOUTCLK}]'. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":63]

[Vivado 12-4739] get_clocks:No valid object(s) found for '--of_objects [get_pins -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GTYE4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST/TXOUTCLK}]'. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":64]

and another seven during implementation:

[Vivado 12-4739] create_clock:No valid object(s) found for '-objects [get_pins -filter REF_PIN_NAME=~TXOUTCLK -of_objects [get_cells -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GT*E4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST}]]'. ["project/pcie_ip_block/source/ip_pcie4_uscale_plus_x0y0.xdc":127]

[Vivado 12-4739] set_clock_groups:No valid object(s) found for '-group [get_clocks -of_objects [get_pins -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GTYE4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST/TXOUTCLK}]]'. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":63]

[Vivado 12-4739] set_clock_groups:No valid object(s) found for '-group '. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":63]

[Vivado 12-4739] set_clock_groups:No valid object(s) found for '-group [get_clocks -of_objects [get_pins -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GTYE4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST/TXOUTCLK}]]'. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":64]

[Vivado 12-4739] set_clock_groups:No valid object(s) found for '-group '. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":64]

[Vivado 12-5201] set_clock_groups: cannot set the clock group when only one non-empty group remains. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":63]

[Vivado 12-5201] set_clock_groups: cannot set the clock group when only one non-empty group remains. ["project/pcie_ip_block/synth/pcie_ip_block_late.xdc":64]

The first warning in each group points at this line in ip_pcie4_uscale_plus_x0y0.xdc, which was automatically generated by the tools:

create_clock -period 4.0 [get_pins -filter {REF_PIN_NAME=~TXOUTCLK} -of_objects [get_cells -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GT*E4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST}]]

And the other at these two lines in pcie_ip_block_late.xdc, also generated by the tools:

set_clock_groups -asynchronous -group [get_clocks -of_objects [get_ports sys_clk]] -group [get_clocks -of_objects [get_pins -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GTYE4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST/TXOUTCLK}]]

set_clock_groups -asynchronous -group [get_clocks -of_objects [get_pins -hierarchical -filter {NAME =~ *gen_channel_container[1200].*gen_gtye4_channel_inst[3].GTYE4_CHANNEL_PRIM_INST/TXOUTCLK}]] -group [get_clocks -of_objects [get_ports sys_clk]]

So this is clearly about a reference to a non-existent logic cell supposedly named gen_channel_container[1200], and in particular that index, 1200, looks suspicious.

I would have been relatively fine with ignoring these warnings had it been just the set_clock_groups that failed, as these create false paths. If the design implements properly without these, it’s fine. But failing a create_clock command is serious, as this can leave paths unconstrained. I’m not sure if this is indeed the case, and it doesn’t matter all that much. One shouldn’t get used to ignoring critical warnings.

Looking at the .xci file for this PCIe block, it’s apparent that several changes were made to it while upgrading to 2020.1. Among those changes, these three lines were added:

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="MODELPARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT">GTHE4_CHANNEL_X49Y99</spirit:configurableElementValue>

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="MODELPARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT_CONTAINER">1200</spirit:configurableElementValue>

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="MODELPARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT_QUAD_INX">3</spirit:configurableElementValue>

Also, somewhere else in the XCI file, this line was added:

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="PARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT">GTHE4_CHANNEL_X49Y99</spirit:configurableElementValue>

So there’s a bug in the upgrading mechanism, which sets some internal parameter to select the a nonexistent GT site.

The manual fix (GUI)

To rectify the wrong settings manually, enter the settings of the PCIe block, and click the checkbox for “Enable GT Quad Selection” twice: Once for unchecking, and once for checking it. Make sure that the selected GT hasn’t changed.

Then it might be required to return some unrelated settings to their desired values. In particular, the PCI Device ID and similar attributes change to Xilinx’ default as a result of this. It’s therefore recommended to make a copy of the XCI file before making this change, and then use a diff tool to compare the before and after files, looking for irrelevant changes. Given that this revert to default has been going on for so many years, it seems like Xilinx considers this a feature.

But this didn’t solve my problem, as the bundle needs to set itself correctly out of the box.

Modifying the XCI file? (Not)

The immediate thing to check was whether this problem applies to PCIe blocks that are created in Vivado 2020.1 from scratch inside a project which is set to target KCU116 (which is what the said Xillybus bundle targets). As expected, it doesn’t — this occurs just on upgraded IP blocks: With the project that was set up from scratch, the related lines in the XCI file read:

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="MODELPARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT">GTYE4_CHANNEL_X0Y7</spirit:configurableElementValue>

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="MODELPARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT_CONTAINER">1</spirit:configurableElementValue>

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="MODELPARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT_QUAD_INX">3</spirit:configurableElementValue>

and

<spirit:configurableElementValue spirit:referenceId="PARAM_VALUE.MASTER_GT">GTYE4_CHANNEL_X0Y7</spirit:configurableElementValue>

respectively. These are values that make sense.

With this information at hand, my first attempt to solve this was to add the four new lines to the old XCI file. This allowed using the XCI file with Vivado 2020.1 properly, however synthesizing the PCIe block on older Vivado versions failed: As it turns out, all MODELPARAM_VALUE attributes become instantiation parameters for pcie_uplus_pcie4_uscale_core_top inside the PCIe block. However looking at the source file (on 2020.1), these parameters are indeed defined (only in those generated in 2020.1), and yet they are unused, like many other instantiation parameters in this module. So apparently, Vivado’s machinery generates an instantiation parameter for each of these, even if they’re not used. Those unused parameters are most likely intended for scripting.

So this trick made Vivado instantiate the pcie_uplus_pcie4_uscale_core_top with instantiation parameters that it doesn’t have, and hence its synthesis failed. Dead end.

I didn’t examine the possibility to deselect “Enable GT Quad Selection” in the original block, because Vivado 2017.3 chooses the wrong GT for the board without this option.

Workaround with Tcl

Eventually, I solved the problem by adding a few lines to the Tcl script.

Assuming that $ip_name has been set to the name of the PCIe block IP, this Tcl snippet rectifies the bug:

if {![string equal "" [get_property -quiet CONFIG.MASTER_GT [get_ips $ip_name]]]} {

set_property -dict [list CONFIG.en_gt_selection {true} CONFIG.MASTER_GT {GTYE4_CHANNEL_X0Y7}] [get_ips $ip_name]

}

This snippet should of course be inserted after updating the IP core (with e.g. upgrade_ip [get_ips]). The code first checks if the MASTER_GT is defined, and only if so, it sets it to the desired value. This ensures that nothing happens with the older Vivado versions. Note the “quiet” flag of get_properly, which prevents it from generating an error if the property isn’t defined. Rather, it returns an empty string if that’s the case, which is what the result is compared against.

Setting MASTER_GT this way also rectifies GT_CONTAINER correctly, and surprisingly enough, this doesn’t change anything it shouldn’t, and in particular, the Device IDs remain intact.

However the disadvantage with this solution is that the GT to select is hardcoded in the Tcl code. But that’s fine in my case, for which a specific board (KCU116) is targeted by the bundle.

Another way to go, which is less recommended, is to emulate the check and uncheck of “Enable GT Quad Selection”:

if {![string equal "" [get_property -quiet CONFIG.MASTER_GT [get_ips $ip_name]]]} {

set_property CONFIG.en_gt_selection {false} [get_ips $ip_name]

set_property CONFIG.en_gt_selection {true} [get_ips $ip_name]

}

However turning the en_gt_selection flag off and on again also resets the Device ID to default as with manual toggling of the checkbox. And even though it sets the MASTER_GT correctly in my specific case, I’m not sure whether this can be relied upon.

Vivado 2025.2 update

Fast forward to late 2025, it turns out that Vivado 2025.2 suddenly reacts to the workaround by selecting the GTY quad to GTY_Quad_227, and resetting the Device ID to its default value. This doesn’t happen with Vivado 2025.1 and back.

Removing the workaround code still resulted in MASTER_GT being set to GTHE4_CHANNEL_X49Y99. However, as of 2025.1, this makes no difference anymore (actually, also as soon as 2023.1). This property doesn’t influence anything of the PCIe block IP’s files, except for the XCI and XML files, where this property has a different value. As it has no influence on the source files used for implementation, the workaround can be removed safely for all versions starting with 2025.1 (and probably earlier too).

So the update workaround looks like this:

if {[version -short] < 2025.1 && \

![string equal "" [get_property -quiet CONFIG.MASTER_GT [get_ips $ip_name]]]} {

set_property -dict [list CONFIG.en_gt_selection {true} CONFIG.MASTER_GT {GTYE4_CHANNEL_X0Y7}] [get_ips $ip_name]

}

The obvious change is that the workaround isn’t applied from Vivado 2025.1 and later.

Introduction

This post examines what the Microsoft’s compiler does in response to a variety of special functions that implement atomic operations and memory barriers. If you program like a civilized human being, that is with spinlocks and mutexes, this is a lot of things you should never need to care about.

I’ve written a similar post regarding Linux, and it’s recommended to read it before this one (even though it repeats some of the stuff here).

To make a long story short:

- The Interlocked-something functions do not just guarantee atomicity, but also function as a memory barrier to the compiler

- Memory fences are unnecessary for the sake of synchronizing between processors

- The conclusion is hence that those Interlocked functions also work as multiprocessor memory barriers.

Trying it out

The following code:

LONG atomic_thingy;

__declspec(noinline) LONG do_it(LONG *p) {

LONG x = 0;

LONG y;

x += *p;

y = InterlockedExchangeAdd(&atomic_thingy, 0x1234);

x += *p;

return x + y;

}

When compiling this as “free” (i.e. optimized), this yields:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 8B 45 08 mov eax,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000008: 8B 10 mov edx,dword ptr [eax]

0000000A: 56 push esi

0000000B: B9 34 12 00 00 mov ecx,1234h

00000010: BE 00 00 00 00 mov esi,offset _atomic_thingy

00000015: F0 0F C1 0E lock xadd dword ptr [esi],ecx

00000019: 8B 00 mov eax,dword ptr [eax]

0000001B: 03 C1 add eax,ecx

0000001D: 03 C2 add eax,edx

0000001F: 5E pop esi

00000020: 5D pop ebp

00000021: C2 04 00 ret 4

First thing to note is that InterlockedExchangeAdd() has been translated into a “LOCK XADD”, which indeed fetches the previous value into ECX and stores the updated value into memory. The previous value is stored in ECX after this operation, which is @y in the C code — InterlockedExchangeAdd() returns the previous value.

XADD by itself isn’t atomic, which is why the LOCK prefix is added. More about LOCK below.

What is crucially important to note, is that putting InterlockedExchangeAdd() between the two reads of *p prevents the optimizations of these two reads into one. @p isn’t defined as volatile, and yet it’s read from twice (ptr [eax]).

Another variant, now trying InterlockedOr():

LONG atomic;

__declspec(noinline) LONG do_it(LONG *p) {

LONG x = 0;

LONG y;

x += *p;

y = InterlockedOr(&atomic, 0x1234);

x += *p;

return x + y;

}

Once again, compiled as “free”, turns into this:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 8B 4D 08 mov ecx,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000008: 8B 11 mov edx,dword ptr [ecx]

0000000A: 53 push ebx

0000000B: 56 push esi

0000000C: 57 push edi

0000000D: BE 34 12 00 00 mov esi,1234h

00000012: BF 00 00 00 00 mov edi,offset _atomic

00000017: 8B 07 mov eax,dword ptr [edi]

00000019: 8B D8 mov ebx,eax

0000001B: 0B DE or ebx,esi

0000001D: F0 0F B1 1F lock cmpxchg dword ptr [edi],ebx

00000021: 75 F6 jne 00000019

00000023: 8B F0 mov esi,eax

00000025: 8B 01 mov eax,dword ptr [ecx]

00000027: 5F pop edi

00000028: 03 C6 add eax,esi

0000002A: 5E pop esi

0000002B: 03 C2 add eax,edx

0000002D: 5B pop ebx

0000002E: 5D pop ebp

0000002F: C2 04 00 ret 4

This is quite amazing: The OR isn’t implemented as an atomic operation, but rather it goes like this: The previous value of @atomic is fetched into EAX and then moved to EBX. It’s ORed with the constant 0x1234, and then the cmpxchg instruction writes the result (in EBX) into @atomic only if its previous value was the same as EAX. If not, the previous value is stored in EAX instead. In the latter case, the JNE loops back to try again.

I should mention that cmpxchg compares with EAX and stores the previous value to it if the comparison fails, even though this register isn’t mentioned explicitly in the instruction. It’s just a thing that cmpxchg works with EAX. EBX is the register to compare with, and it therefore appears in the instruction. Confusing, yes.

Also here, *p is read twice.

It’s also worth noting that using InterlockedOr() with the value 0 as a common way to grab the current value yields basically the same code (only the constant is generated with a “xor esi,esi” instead).

So if you want to use an Interlocked function just to read from a variable, InterlockedExchangeAdd() with zero is probably better, because it doesn’t create all that loop code around it.

Another function I’d like to look at is InterlockedExchange(), as it’s used a lot. Spoiler: No surprises are expected.

LONG atomic_thingy;

__declspec(noinline) LONG do_it(LONG *p) {

LONG x = 0;

LONG y;

x += *p;

y = InterlockedExchange(&atomic_thingy, 0);

x += *p;

return x + y;

}

and this is what it compiles into:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 8B 45 08 mov eax,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000008: 8B 10 mov edx,dword ptr [eax]

0000000A: 56 push esi

0000000B: 33 C9 xor ecx,ecx

0000000D: BE 00 00 00 00 mov esi,offset _atomic_thingy

00000012: 87 0E xchg ecx,dword ptr [esi]

00000014: 8B 00 mov eax,dword ptr [eax]

00000016: 03 C1 add eax,ecx

00000018: 03 C2 add eax,edx

0000001A: 5E pop esi

0000001B: 5D pop ebp

0000001C: C2 04 00 ret 4

And finally, what about writing twice to the same place?

LONG atomic_thingy;

__declspec(noinline) LONG do_it(LONG *p) {

LONG y;

*p = 0;

y = InterlockedExchangeAdd(&atomic_thingy, 0);

*p = 0;

return y;

}

Writing the same constant value twice to a non-volatile variable. This calls for an optimization. But the Interlocked function prevents it, as expected:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 8B 4D 08 mov ecx,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000008: 83 21 00 and dword ptr [ecx],0

0000000B: 33 C0 xor eax,eax

0000000D: BA 00 00 00 00 mov edx,offset _atomic_thingy

00000012: F0 0F C1 02 lock xadd dword ptr [edx],eax

00000016: 83 21 00 and dword ptr [ecx],0

00000019: 5D pop ebp

0000001A: C2 04 00 ret 4

Writing a zero is implemented by ANDing with zero, so it’s a bit confusing. But it’s done twice, before and after the “lock xadd”. Needless to say, these two writes are fused into one by the compiler without the Interlocked statement in the middle (I’ve verified it with disassembly, 32 and 64 bit).

Volatile?

In Microsoft’s definition for the InterlockedExchangeAdd() function (and all other similar ones) is that the first operand is a pointer to a LONG volatile. Why volatile? Does the variable really need to be?

The answer is no, if all accesses to the variable is made with Interlocked-something functions. There will be no compiler optimizations, not on the call itself, and the call itself is a compiler memory barrier.

And it’s a good habit to stick to these functions, because of this implicit compiler memory barrier: That’s usually what we want and need, even if we’re not fully aware of it. Accessing a shared variable almost always has a “before” and “after” thinking around it. The volatile keyword doesn’t protect against reordering optimizations by the compiler (or otherwise).

But if the variable is accessed without these functions in some places, the volatile keyword should definitely be used when defining that variable.

More about LOCK

It’s a prefix that is added to an instruction in order to ensure that it’s performed atomically. In many cases, it’s superfluous and sometimes ignored, as the atomic operation is ensured anyhow.

From Intel’s 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 2 (instruction set reference) vol. 2A page 3-537, on the “LOCK” prefix for instructions:

Causes the processor’s LOCK# signal to be asserted during execution of the accompanying instruction (turns the instruction into an atomic instruction). In a multiprocessor environment, the LOCK# signal ensures that the processor has exclusive use of any shared memory while the signal is asserted.

The manual elaborates further on the LOCK prefix, but says nothing about memory barriers / fences. This is implemented with the MFENCE, SFENCE and LFENCE instructions.

The LOCK prefix is encoded with an 0xf0 coming before the instruction in the binary code, by the way.

Linux counterparts

For x86 only, of course:

- atomic_set() turns into a plain “mov”

- atomic_add() turns into “lock add”

- atomic_sub() turns into “lock sub”

I’m not sure that there are any Windows functions for exactly these.

Is a memory barrier (fences) required?

Spoiler: Not in x86 kernel code, including 32 and 64 bits. Surprise. Unless you really yearn for a headache, this is the right place to stop reading this post.

The theoretical problem is that each processor core might reorder the storing or fetching of data between registers, cache and memory in any possible way to increase performance. So if one one processor writes to X and then Y, and it’s crucial that the other processor sees the change in Y only when it also sees X updated, a memory barrier is often used. In the Linux kernel, smp_wmb() and smp_rbm() are used in conjunction to ensure this.

For example, if X is some data buffer, and Y is a flag saying that the data is valid. One processor fills the buffer X and then sets Y to “valid”. The other processor reads Y first, and if it’s valid, it accesses the buffer X. But what if the other processor sees Y as valid before it sees the data in X correctly? A store memory barrier before writing to Y and a read memory barrier before reading from X ensures this.

The thing is, that the Linux kernel’s implementation of smp_wmb() and smp_rbm() for x86 is a NOP. Note that it’s only the smp_*() versions that are NOPs. The non-smp fences turn into opcodes that implement fences. Assuming that the Linux guys know what they’re doing (which is a pretty safe assumption in this respect) they’re telling us that the view of ordering is kept intact across processor cores. In other words, if I can assure that X is written before Y on one processor, then Intel promises me that on another processor X will be read with the updated value before Y is seen updated.

Looking at how Microsoft’s examples solve certain multithreading issues, it’s quite evident that they trust the processor to retain the ordering of operations.

Memory fences are hence only necessary to ensure the ordering on a certain processor on x86. On different architectures (e.g. ARM v7) smp_wmb() and smp_rbm() actually do produce some code.

When are these fences really needed? From Intel’s 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 2 (instruction set reference) vol. 2A page 4-22, on the “MFENCE” instruction:

Performs a serializing operation on all load-from-memory and store-to-memory instructions that were issued prior the MFENCE instruction. This serializing operation guarantees that every load and store instruction that precedes the MFENCE instruction in program order becomes globally visible before any load or store instruction that follows the MFENCE instruction. The MFENCE instruction is ordered with respect to all load and store instructions, other MFENCE instructions, any LFENCE and SFENCE instructions, and any serializing instructions (such as the CPUID instruction).

That didn’t answer much. I searched for fence instructions in the disassembly of a Linux kernel compiled for x86_64. A lot of fence instructions are used in the initial CPU bringup, in particular after setting CPU registers. Makes sense. Then there are several other fence instructions in drivers, which aren’t necessarily needed, but who has the guts to remove them?

Most interesting is where I didn’t find a single fence instruction: In any of the object files generated in kernel/locking/. In other words, Linux’ mutexes and spinlocks are all implemented without any fence. So this is most likely a good proof that they aren’t needed for anything else but things related to the CPU state itself. I guess. For a 64-bit x86, that is.

Going back to Microsoft, it’s interesting that their docs for userspace Interlocked functions say “This function generates a full memory barrier (or fence) to ensure that memory operations are completed in order”, but not those for kernel space. Compare, for example InterlockedOr() for applications vs. the same function for kernel. Truth is I didn’t bother to do the same disassembly test for application code.

Some barriers functions

(or: A collection of functions you probably don’t need, even if you think you do)

- KeFlushWriteBuffer(): Undocumented and rarely mentioned, intended for internal kernel use. Probably just makes sure that the cache has been flushed (?).

- KeMemoryBarrier(): Calls _KeMemoryBarrier(). But in wdm.h, there’s an implementation of this function, calling FastFence() and LoadFence(). But these are just macros for __faststorefence and _mm_lfence. Looked at next.

- _mm_lfence() : Turns into an lfence opcode. Same as rmb() in Linux.

- _mm_sfence(): Turns into an sfence opcode. Same as wmb() in Linux.

- _mm_mfence(): Turns into an mfence opcode.

I’ve verified that the _mm_*fence() builtins generated the said opcodes when compiled for x86 and amd64 alike. See some experiments on this matter below.

The deprecated _ReadBarrier(), _WriteBarrier() and _ReadWriteBarrier() produce no code at all. MemoryBarrier() ends up as a call to _MemoryBarrier().

Experimenting with fence instructions

(or: A major waste of time)

This is the code compiled:

__declspec(noinline) LONG do_it(LONG *p) {

LONG x = 0;

x += *p;

_mm_lfence();

x += *p;

return x;

}

With a “checked compiation” this turns into:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 51 push ecx

00000006: C7 45 FC 00 00 00 mov dword ptr [ebp-4],0

00

0000000D: 8B 45 08 mov eax,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000010: 8B 4D FC mov ecx,dword ptr [ebp-4]

00000013: 03 08 add ecx,dword ptr [eax]

00000015: 89 4D FC mov dword ptr [ebp-4],ecx

00000018: 0F AE E8 lfence

0000001B: 8B 55 08 mov edx,dword ptr [ebp+8]

0000001E: 8B 45 FC mov eax,dword ptr [ebp-4]

00000021: 03 02 add eax,dword ptr [edx]

00000023: 89 45 FC mov dword ptr [ebp-4],eax

00000026: 8B 45 FC mov eax,dword ptr [ebp-4]

00000029: 8B E5 mov esp,ebp

0000002B: 5D pop ebp

0000002C: C2 04 00 ret 4

OK, this is too much. There is no ptimization at all. So let’s look at the “free” compilation instead:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 8B 45 08 mov eax,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000008: 8B 08 mov ecx,dword ptr [eax]

0000000A: 0F AE E8 lfence

0000000D: 8B 00 mov eax,dword ptr [eax]

0000000F: 03 C1 add eax,ecx

00000011: 5D pop ebp

00000012: C2 04 00 ret 4

So clearly, the fence command made the compiler read the value from memory twice, as opposed to optimizing the second read away. Note that there’s no volatile keyword involved. So except for the fence, there’s no reason to read from *p twice.

The exact same result is obtained with _mm_mfence().

Trying with _mm_sfence() yields an interesting result however:

_do_it@4:

00000000: 8B FF mov edi,edi

00000002: 55 push ebp

00000003: 8B EC mov ebp,esp

00000005: 8B 45 08 mov eax,dword ptr [ebp+8]

00000008: 8B 00 mov eax,dword ptr [eax]

0000000A: 0F AE F8 sfence

0000000D: 03 C0 add eax,eax

0000000F: 5D pop ebp

00000010: C2 04 00 ret 4

*p is read into eax once, then the fence, and then it’s added by itself. As opposed to above, where it was read into eax before the fence, then read again into ecx, and then added eax with ecx.

So the compiler felt free to optimize the two reads into one, because the store fence deals only with writes into memory, not reads. Given that there’s no volatile keyword used, it’s fine to optimize reads, which is exactly what it did.

The same optimization occurs if the fence command is removed completely, of course.

For the record, I’ve verified the equivalent behavior on the amd64 target (I’ll spare you the assembly code).

This baffled me for a while: I used certmgr to see if a Windows 10 machine had a root certificate that was needed to certify a certain digital signature, and it wasn’t listed. But then the signature was validated. And not only that, the root certificate was suddenly present in certmgr. Huh?

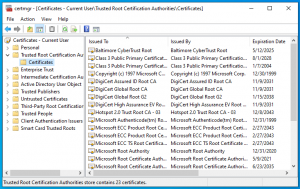

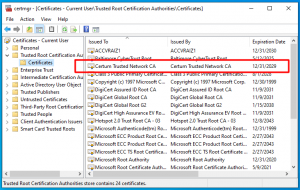

Here’s a quick demonstration. This is the “before” screenshot of the Certificate Manager window (click to enlarge):

Looking at the registry, I found 11 certificates in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\SystemCertificates\AuthRoot\Certificates\ and 12 certificates in HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\SystemCertificates\ROOT\Certificates\, so it matches exactly certmgr’s view of 23 root certificates.

And so I had a .cab file with a certificate that requires Certum’s root certificate for validation. Clear from the screenshot above, it’s not installed.

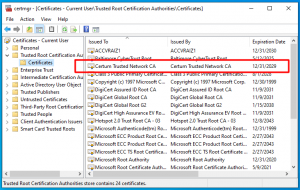

Then I right-clicked that .cab file, selected Properties, then the “Digital Signature Tab”, selected the certificate and clicked Details, and boom! A new root certificate was automatically installed (click to enlarge):

And suddenly there are 12 certificates in the AuthRoot part of the registry instead of 11. Magic.

And here’s the behind the scenes of that trick.

Microsoft publishes a Certificate Trust List (CTL), which every computer downloads automatially every now and then (once a week, typically). It contains the list of root authorities that the computer should trust, however apparently they are imported into the registry only as needed. This page describes the concept of CTL in general.

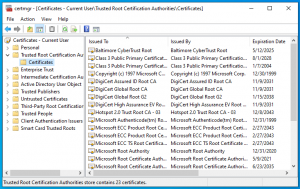

I don’t know where this is stored on the disk, however one can download the list and create an .sst file, which opens certmgr when double-clicked. That lists all certificates of the downloaded CTL. 425 of them, as of May 2021, including Certum of course:

> certutil -generateSSTFromWU auth.sst

So it seems like Windows installs certificates from the CRL as necessary to validate certificate chains. This includes the GUI for examining certificates, verifying with signtool, as well as requiring the certificate for something actually useful.

There’s also a utility called CTLInfo out there, which I haven’t tried. It apparently displays the CTL currently loaded in the system, but I haven’t tried it out.

There’s another post in Stackexchange on this matter.

Besides, I’ve written a general post on certificates, if all this sounded like Chinese.

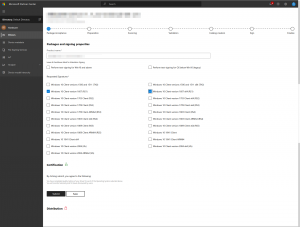

Introduction

This is my best effort to summarize the steps to attestation signing for Windows drivers (see Microsoft’s main page on this). I’m mostly a Linux guy with no connections inside Microsoft, so everything written below is based upon public sources, trial and (a lot of) error, some reverse engineering, and speculations. This couldn’t be further away from the horse’s mouth, and I may definitely be wrong occasionally (that is, more than usual).

Also, the whole topic of attestation signature seems to be changing all the time, so it’s important to keep in mind that this reflects the situation of May 10th 2021. Please comment below as things change or whenever I got things wrong to begin with.

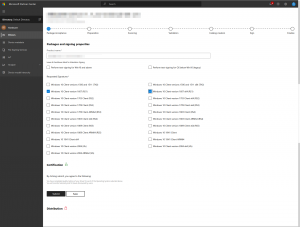

Attestation signing replaces the method that was available until April 2021, which was signing the driver locally by its author, just like any code signing. With attestation signing, Microsoft’s own digital signature is used to sign the driver. To achieve that, the driver’s .inf and .sys files are packed in a .cab file, signed by the author, and submitted to Microsoft. Typically 10 minutes later, the driver is signed by Microsoft, and can be downloaded back by the author.

Unfortunately, the signature obtained this way is recognized by Windows 10 only. In order to obtain a signature that works with Windows 7 and 8, the driver needs to get through an HLK test.

Signing up to the Hardware Program

This seemingly simple first step can be quite confusing and daunting, so let’s begin with the most important point: The only piece of information that I found present in Microsoft’s output (i.e. their signature add-ons), which wasn’t about Microsoft itself, was the company’s name, as I stated during the enrollment. In other words, what happens during the sign-up process doesn’t matter so much, as long as it’s completed.

This is Microsoft’s general how-to page for attestation signing in general, and this one about joining the hardware program. It wasn’t clear to me from these what I was supposed to do, so I’ll try to offer some hints.

The subscription to the Hardware Program can begin when two conditions are met:

- You have the capability to sign a file with an Extended Validation (EV) code signing certificate.

- You have an Azure Active Directory Domain Services managed domain (“Azure AD”).

Obtaining an EV certificate is a bureaucratic process, and it’s not cheap. But at least the other side tells you what to do, once you’ve paid. I went for ssl.com as their price was lowest, and working with them I got the impression that the company has hired people who actually know what they do. In short, recommended. Actually, read this first if you plan working with them.

So what’s the Domain Services thing? Well, this is the explanation from inside the Partner web interface (once it has already been set up): “Partner Center uses Azure Active Directory for identity and access management”. That’s the best I managed to find on why this is necessary.

For a single user scenario, this boils down to obtaining a domain name like something.onmicrosoft.com from Microsoft. It doesn’t matter if the name turns out long and daunting: It doesn’t appear anywhere else, and you’re not going to type it manually.

So here’s what to do: First thing first, create a fresh Microsoft account. Not really necessary if you already have one, but there’s going to be quite some mail going its way (some of which is promotional, unless you’re good at opting out).

Being logged into that account, start off on Azure’s main page. Join the 12-month free trial. It’s free, and yet you’ll need to supply a valid credit card number in the process. As of writing this, I don’t know what happens after 12 months (but see “Emails from Azure calling for an upgrade” below on developments).

The next step is to create that domain service. I believe this is Microsoft’s page on the topic, and this is the moment one wonders why there’s talk about DNSes and virtual networks. Remember that the only goal is to obtain the domain name, not to actually use it.

And here comes the fuzzy part, where I’m not sure I didn’t waste time with useless operations. So you may try following this, as it worked for me. But I can’t say I understand why these seemingly pointless actions did any good. I suspect that the bullets in italics below can be skipped — maybe it’s just about creating an Azure account, and not necessarily allocate resources?

So here are the steps that got me going:

- Log in to your (new?) Azure account.

- Go to Azure’s Portal (or click the “Portal” link at the top bar on Azure’s main page)

Maybe skip these steps (?):

- Click “Create a resource” (at the top left) and pick Azure AD Domain Services.

- For Resource Group I created a new one, “the_resource_group”. I guess the name doesn’t matter.

- The DNS name doesn’t matter, apparently. yourcompany.onmicrosoft.com or something. It’s not going to appear anywhere.

- I set SKU set to Standard, as it appeared to be the least expensive one.

- After finishing the setup, it took about an hour for Azure to finish the configuration. Time for a long and well deserved coffee break.

- But then it complained that I need to set up DNSes or something. So I went along with the automatic fix.

(end of possibly useless steps)

- There’s this thing on the Register for the Hardware Program page saying that one should log in with the Global administrator account. This page defines Azure AD Global administrator as “This administrator role is automatically assigned to whomever created the Azure AD tenant”. So apparently for a fresh Azure account, it’s OK as is.

- At this point, you’re hopefully set to register to the Hardware Developer Program. After clicking “Next” on the landing page, you’ll be given the choice of “Sign in to Azure AD” or “Create a new directory for free”. The Azure AD is already set up, so log in with the account just created.

- A word about that “Create a new directory for free” option. To make things even more confusing, this appears to be a quick and painless shortcut, however in my case I got “This domain name is not available” for any domain name I tried with. Maybe I missed something, but this was a dead end for me. This is the page I didn’t manage to get through. Maybe your luck is better than mine. So this is why I created the Azure AD first, and then went for registration.

- Going on with the registration, you’re given a file to sign with your EV certificate. I got a .bin file, but in fact it had .exe or .sys format. So it can be renamed to .exe and used with cloud signature services (I used eSigner). BUT do this only if you’re going to sign the .cab files with the same machinery, or you’ll waste a few hours wondering what’s going on. Or read below (“When the signature isn’t validated”) why it was wrong in my case.

- And this is the really odd thing: Inside the Microsoft Partner Center, clicking the “your account” button (at the top right) it shows the default directory in use. At some point during the enrollment procedure, the link with the Azure AD I created was made (?), but for some reason, the default directory shown was something like microsoftazuremycompany.onmicrosoft.com instead of mycompany.onmicrosoft.com, which is the domain I created before. This didn’t stop me from signing a driver. So if another directory was used, why did I create one earlier?

After all this, I was set to submit drivers for signature: From this moment on, the entry point for signing drivers is the Microsoft Partner Center dashboard’s main page.

Emails from Azure calling for an upgrade