Internet fiber optics in Israel: The gory technical details

Introduction

In July 2023 I finally decided to ditch my ADSL connection and upgrade to fiber optics (FTTH). Living in Israel, the whole thing gets a bit complicated, because there’s a separation between the infrastructure provider and the ISP. In other words, the fiber connections is supplied by company A, which brings the connection to the doorsteps of company B, the ISP, which takes care of the connection to the world. A and B can be the same company, but they often aren’t.

In my case, Bezeq is the provider of the fiber connection itself, and I’ve chosen Netvision / Cellcom as the ISP. The technical details below may be significantly different for you, in particular if another company has done the fiber infrastructure. There seems to be a lot of confusion regarding the infrastructure part, possibly because different service providers do things differently. I don’t know. This post is all about my own Internet connection.

There are three reasons why I got so involved in the gory details of this:

- It pays off in the long run. In particular, on that day when the Internet link falls, you call customer support and they are clueless (as always). If I can figure out what the problem is based upon my understanding of the system and the information that my own equipment provides, the link has a chance to get back quickly. Otherwise, good luck. And yes, it’s their job to know what they’re doing, but that’s nice in theory.

- There was some problem with ordering the service. It’s not clear exactly why, but it seems like a new fiber splitter was needed in the floor connection box (more on that below). It took a month from my first phone call to the actual installation.

- This stuff is actually interesting, and somewhat related to things I do for a living. I didn’t become an electrical engineer for nothing.

Reason #1 above implies working with equipment that exposes technical information. Sweet-talking routers that are configured automatically by virtue of a mobile phone app may be quick to set up, but then go figure what’s going on when something goes wrong. The fiber front-end should be as simple as possible and yet provide diagnostic information, at best.

Acronyms

I’m going to use these, so let’s get this over with:

- PON (Passive optical network) is the standard that arranges fiber connections in a one-to-many topology.

- GPON: Gigabit-capable PON. A standard on top of PON, which makes it capable for carrying Gigabit Ethernet.

- ONT: Optical Network Terminal. That is the little box we have in our homes. Sometimes called “fiber modem”, “fiber adapter”. Even a router is some kind of ONT.

- OLT: Optical Line Terminal: That’s the electronics that is connected to the fiber somewhere in the company’s premises.

- FTTH: Fiber to the home. A commercial term with obvious meaning.

The technical details in brief

The fiber connection is PON with an SC/APC connector (used for Gigabit Ethernet, hence GPON). I’m discussing this to painstaking detail below, so for now we’ll do with the fact that only one fiber is used for full-duplex communication. Unlike the SFP+ configuration I’m used to, which carries two fibers with a slinky feel, and usually connects with a dual connector, a GPON fiber looks like a somewhat rigid wire, and has a connector with a square shape.

But the most important technical detail is that pppoe is used. Effectively, the look and feel is exactly like ADSL, only it’s faster. Just like with ADSL, you get a username and a password. If you have a router, the credentials go there. But if you opted that out like I did, and instead went for an simple ONT (a.k.a. “fiber adapter”, “ONT bridge”, “fiber modem”), the computer needs to do the pppoe stuff (or maybe an pppoe-capable router, but what’s the point?).

As it turns out, the only thing I needed to change in my existing pppoe setting was the username and password.

Well, no. Doing that is enough to get a working Internet connection with an impressive data rate, but not even close to the advertised rate. To attain that, I had to switch to using the kernel’s pppoe module, as detailed in a separate post.

As a side note, my original plan was to have ADSL and fiber optics running for a month in parallel, just to be safe. But as soon as I got the fiber account activated (see below), the ADSL stopped working. Even though I asked explicitly to keep both accounts active in parallel, and even though the username for fiber was different from the one I used for ADSL (albeit very similar), ADSL got knocked down. I guess I asked for too much. Because it went so easily with the fiber, I wasn’t in the mood to waste time on ensuring redundancy.

Speed tests

There are two interesting sites for this:

- Netvision’s own speed test. I got 930 Mb/s down and 100 Mb/s up on this test. Quite reasonable.

- Ookla’s speed test allows choosing which server to run against. So picking Bezeq’s server, for example, I got 500 Mb/s down and 100 Mb/s up. This says nothing more than the connections between Cellcom and Bezeq.

Downloading a huge from from ISOC’s mirror server gave me around 400 Mb/s.

So the 1000 Mb/s figure is nice, but theoretical. And that’s before starting with server’s abroad. For example, downloading a huge file from a server in Germany (which is considered relatively close), the rate began at ~80 Mbit/s, and slowly rose towards 320 Mb/s. Which isn’t bad, actually.

GPON in a nutshell

GPON is a one-to-many framework. It means that the service provider (OLT) broadcasts a single 2.4 Gbit/s downstream signal to all subscribers (up to 128). Optical splitters divide this signal among the physical fibers that reach the subscribers. Likewise, all upstream signals are optically combined on their way to the OLT’s optical sensor. A 1.2 Gbit/s stream is TDMA’ed among the subscribers to avoid collisions. Each frame on the fiber is 125 μs, in both directions.

Each subscriber is connected with only one fiber, with a separate light wavelength for each direction: 1490 nm downstream, 1310 nm upstream (both infrared, hence invisible even with my smartphone’s camera).

The handshake that sets up the GPON link usually takes less than a second, but it involves several stages. During this setup, the ONT’s unique serial number is transmitted to the OLT. This means that the provider of the fiber network service can identify each subscriber, regardless of how the fibers are connected. It also means that if the ONT is replaced with another similar box, there will probably be a need to inform the service provider about the updated serial number, or else it will be rejected.

Like any TDMA protocol, the transmission of upstream data must be orchestrated and synchronized. As there might be significant differences between the fibers’ lengths, a calibration process called ranging takes place soon after the fiber is connected to the ONT. This allows compensating for these differences, and ensure an accurate timing of the upstream frames.

The immediate conclusion is that we share bandwidth with our neighbors. How many neighbors and which ones, that depends on how the optical splitting is made, but in most realistic scenarios, the data bottleneck will not be on the fiber: For now, the Internet itself isn’t all that fast, after all.

But if someone has a faulty ONT that transmits data when it shouldn’t (or say, all the time), this can definitely knock down a few neighbor’s connection. Not likely to happen, and still.

Is the pppoe handshake necessary?

I’ve seen talk about users getting a “DHCP connection” over fiber. It’s not clear if they got confused with the fact that their router at home gave them an IP address, or if some people skip the pppoe thing, and talk with a DHCP server across the fiber link.

Given that the bringup of the GPON link involves the ONT’s identification with its serial number, one could argue that the pppoe negotiation is unnecessary: The OLT knows who it is talking with, based upon the serial number. But skipping pppoe requires that OLT does the pairing with the ISP based upon the serial number, rather than the username (which includes the name of the ISP).

So ditching the pppoe thing is surely possible theoretically, and it would surely make things simpler. I don’t know if it has been done in Israel, though.

The fiber/Ethernet “adapter”

If you read my short discussion about GPON above, you’ve realized that there is no such thing as an “fiber to Ethernet adapter” on a GPON system. It’s an ONT, at it’s a very active device. The word “adapter” would have been suitable had the fiber connection been plain Gigabit Ethernet over fiber, with an SFP+ connector, because in that case the adapter indeed just translates the optical signal into an electrical one. But this is definitely not the case with the fibers I had installed.

To my technician’s disappointment, I didn’t want to take Cellcom’s all-in-one router, but requested what is called an “adapter” or “fiber modem” instead. There’s actually a price reduction for going this way, but this wasn’t my motivation: I want the computer to do the pppoe, so I can see what happens.

So the technician gave me a Nokia 7368 ISAM ONT G-010G-Q. It’s a small box with four LEDs. Looked a bit old and used, actually.

The most important thing to know about this box is that it takes about 60 seconds for this thing to boot after powerup.

During this time, the PON LED remains off no matter what, even if the fiber is connected correctly. After these 60 seconds, the “Alarm” LED (red) gets on briefly, after which the PON LED will also go on (if the fiber is connected). A disconnection of the fiber causes the “Alarm” LED to go on, and PON go off. Reconnecting the fiber reverses this (the PON will flash for a second before getting steady). All this is regardless of the LAN LED, which depends on the Ethernet plug, of course.

So a good way to get confused with this box is to turn it on with the fiber connected, see that PON doesn’t go on, and then start doing things randomly, possibly turning the box off and on again. 60 seconds is longer than most of us expect, and the box doesn’t give any indication that it’s starting up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that when the PON LED flashes, it means that a physical connection has been detected, and the box is busy bringing up the data link. When it stays in this state for a long time, it may be because the OLT (the fiber service provider) doesn’t recognize the ONT’s serial number, and therefore refuses to continue the bringup process. During my installation, this was the situation for quite a few minutes, while the technician was on the phone, reading out the ONT’s serial number, among others.

The disadvantage with this Nokia box is that it apparently has no admin interface on the Ethernet side. So it gives me no diagnostic information.

So I got myself a ZTE F601 for $20 instead. It’s listed in Bezeq’s list of approved ONTs, and it has an administration interface that is accessible with a web browser. This interface allows changing the PON serial number, and a whole lot of other things. I’ve written about ZTE’s ONT in a separate post. Bottom line: It’s a nice thing, and I use it instead of Nokia’s ONT. Apparently, the only drawback it has is that the PON LED can be misleading. I elaborate on that on the said post.

But after three weeks with this ONT, I got a phone call from my ISP. They asked me to move back to the Nokia ONT, or Bezeq would disconnect me. I responded by sending the said list of supported ONTs as well as a screenshot of the web interface screen, which shows that the version is correct. However, that didn’t help: Apparently, Bezeq don’t agree that Cellcom users have something different than what’s listed, and they surely didn’t like that I played with the serial number. Or maybe was it Cellcom who didn’t like my games, and they just blamed Bezeq?

I left a brief complaint at Bezeq’s website, and soon enough I got a phone call from their representative. I explained the situation, and a couple of days later, they were back with a clear message: Bezeq has no problem with my ONT, and they had specifically checked my connection and verified that there had been nothing odd reported regarding it.

So it looks like Cellcom doesn’t like my ONT, and they blamed Bezeq for it. Anyhow, I moved back to the Nokia thingy. ZTE will be used as a fallback and for debugging if necessary. It’s not worth my time and effort to fight about this. And the fact that representatives of communication companies make up stories is not really new.

Fun fact: The PPPoE session remained even after replacing the ONT. There was no need to re-initiate it.

Note to self: I left the firewall rules that allow communication with the ZTE ONT.

Choosing ISP

There are several companies in Israel that offer “Internet over Fiber”. One needs to keep in mind that choosing an ISP has an impact on exactly three factors:

- The data rate. The ISP supplies the facilities for routing to the traffic to the world. So except for local services (local TV stations etc. or services that have local servers for better performance), it’s the amount of bandwidth that the ISP has purchased for its connection with Europe and USA that matters.

- The annoyances. Does the ISP block certain types of traffic, for example Bittorrent? Does it “accidentally” disconnect your session in the middle of very long downloads? Does it block certain ports “for your safety”?

- The customer support. Eventually, you’ll have to call someone. How will that work?

I’ve been a Netvision (Cellcom) customer for a very long time, and I’m pretty satisfied with them. So the natural choice is to stay with them.

I did check with Partner, though. The people I got to talk with were exceptionally unprofessional. The person who called me up in response to my interest was very nice, but had no idea what I talked about when I said that I wanted an “adapter” and not a router. I was then handed over to their more technical guy who told me that nobody offers a fiber connection without a router (something Netvision had already approved they’ll do). So Partner was out, because they only offer their router.

I can actually understand that ISPs want to use their own router. All the technical hocus-pocus (activating the ONT’s serial number + setting up the pppoe username and password) is done with a simple mobile app, when using this kind of router. It also makes it a bit more complicated to move from one ISP to another, because I suppose each company locks its routers to its own services (or at least, doesn’t allow this automatic setup to another service). So even though you are legally free to change ISP, it’s still not something you can do with a simple phone call, and boom, you moved. A technician needs to pay a visit. This slows down the migration process, which gives the losing ISP a chance to do the sweet talk. With a neutral ONT, I can change ISP just like that. To an ISP that doesn’t require their own router, of course.

The third alternative that I checked was Bezeq. Their price was high, and my long-time experience with this company is to have as little as possible to do with them.

But I did consider them because of completely different reason: My first call to Cellcom for installing fiber was a month before the actual installation. On this initial call, the sales shark at the other end said that there’s an infrastructure issue that needs to be solved, and promised to come back to me soon. Two weeks passed, and I tried my luck again. Another guy said basically the same, said that he had begun the process of fixing the infrastructure issue, and then disappeared too. I tried again after a week, and this second guy finally opened a call for a technician to install fiber at my place.

A couple of days later, I got a call from Cellcom. This time they wanted to cancel the technician call, because there were missing details, which indicates an infrastructure problem. I refused, and told them to send a technician, and once he arrives, we’ll figure out why there’s a problem.

Eventually, this technician arrived and made the installation.

But why did it take a month? As I’ll detail below, there were already four fiber subscribers in my building. In order to add another one, there was a need to add another fiber splitter in the connection box at the bottom floor. It looks like it was added during this month, not clear when. But it’s clear who did it: Bezeq. It’s quite likely that Bezeq was reluctant to send their technician to allow the connection of a Cellcom subscriber, or maybe their technicians are busy, so they prioritize their own subscribers.

So had I known then what I know today (see below), I would have looked at the connection box and understood the problem. I would then have requested an installation of Bezeq’s fiber service. One day before the arrival of the technician, I would have checked if they had added the splitter, and if so, canceled the installation. If not, I would have let Bezeq’s technician do the fiber installation, and then switched ISP.

The installation process

The rest of this post is dedicated to the art of connecting fibers. In detail, maybe too much detail.

Note to self: See misc-after-moving-here/fiber-internet directory for a few even more specific details.

I’ll start with pointing out that my technician uses the word for “fiber” (“סיב”) to refer to a fiber cable. He uses the word for “leg” (“רגל”) in reference to a single fiber.

And now to what he actually did: The first step is to draw a single fiber from the requested point inside the apartment to the connection box outside the apartment, but on the same floor. In my case, that consisted of pulling the fiber through the existing cable pipes, side-by-side (or instead of) cables for cable TV and good old analog landline telephone.

As it was done in my case, the fiber just pops out from the lower edge of the telephone line jack’s plastic frame, going straight downwards. Not very elegant, but in my specific setting that’s barely visible.

The next step is to make a male optical connector on both sides of the fiber. There are special tools for that.

At this point, a red laser is connected to the fiber inside the apartment, using the connector. This will be used later.

Now to the connection box outside the apartment: It’s manufactured by Appletec (this is a Youtube video showing how to install it + some fiber soldering and stuff). The idea is that a fiber cable is drawn from a box at the bottom floor to the top floor. On each floor, a number of fibers end at that floor’s connection box, one fiber for each apartment. These fibers are connected to female connectors on this box.

So the fiber from my apartment was connected to the floor’s connection box by mating two connectors. Now there’s an optical connection all the way to the connection box at the bottom floor. This is where all fibers from the building arrive, but even more important, this is where Bezeq’s fiber cable (or cables) arrive from their main switch (which can be literally miles away).

This connection box, which I’ll discuss in detail in the next section, is a patch panel for connecting between the fibers from the house to fibers that are connected to Bezeq. All fibers are connected to female connectors, so in order to connect an apartment to Bezeq, a short fiber cable, with two male connectors, is connected between two points.

The tricky part is to tell which of the fibers in this patch panel is connected to my apartment. Well, not really tricky, because of that red laser that was connected to that fiber inside my apartment. So there’s a clear red light showing which one to go on with.

A sticker with details is put on the fiber in both connection boxes. Both stickers containing the same information. It seems like Cellcom’s method is to write the apartment number, the floor, the “tag” number (“מספר תג”) and the Cellcom customer’s number. Partner appear to write the name of the subscriber and nothing else. I have no idea how Bezeq do their marking, because none of my neighbors was stupid enough to choose them. Anyhow, it’s a matter of time before the bottom connection box becomes a snakesnest. Not to mention that it’s practically accessible to anyone.

The floor level connection box

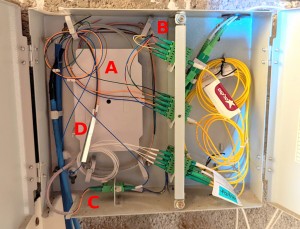

This box is manufactured by Appletec as well. Here’s a picture of its interior: (click to enlarge)

Quite evidently, this box is divided into a left and right compartment, each having a separate door. The intention is most likely that subscription installers keep themselves to the right side, and the infrastructure guys do their stuff to the left.

The first problem that is tackled at the left side of this box is that the fibers that are packed into a cable are too fragile to handle directly. The solution is to insert the cables into a protected enclosure (which I’ve marked A on the photo). In this closure, fusion splice (which is a bit like soldering or welding) is used to make 1:1 connections between the fragile fibers and fibers that have a mechanical protection shield (a thin coating, similar to electrical wire’s isolation). The latter fibers can then be used for the “wiring”. To get an idea what happens inside this enclosure, check out this Youtube video.

There are two types of cables that arrive to this box: Those from the upper floors and those from Bezeq. All these fibers get into this same little enclosure, get their thing done, and then it’s up to the technician who set up the connection box to not get confused about which fibers are which.

I’ve marked a few highlights in this box’ left side in the photo above:

- A: Inside this little plastic enclosure, there are 1:1 connections between fibers from cables and the fibers that are used inside the left side of the connection box. Explained above.

- B: Group of all fibers connected from upper floors (coming from 1:1 connections with cable).

- C: Group of fibers connected to Bezeq’s cable. There are only two of them.

- D: This metal rod is one of two 1:4 splitters in the connection box. The blue fiber at this splitter’s bottom comes from one of the fibers at C (it makes a nice loop on the way there), and the four outputs go to the patch panel’s front. The other 1:4 splitter, which was most likely installed earlier, is lying down on the box’ floor, close to the letter C, and is the output of the four white fibers.

So there are two 1:4 splitters in this connection box. The differences in the colors of the fibers and the way they are laid out in the box indicate that they were installed in different occasions. It seems like the one hanging vertically was installed lately in order to allow for my installation, which is the fifth subscriber on this box.

The right side is supposed to be a patch panel. One could have expected some kind of order, like an upper row of fiber connectors for connections to apartments and a lower row for connections to Bezeq. The reality in this box is not just that there’s no visible distinction, but that the genius who set up this box mixed them up completely. Some kind of note on the box saying which connection is what is of course way too much to expect, even though the slots are numbered.

At the moment there are only 8 live fibers from Bezeq available at the patch panel’s front (i.e. the wall between the left and right parts), so it’s quite likely that one of the fibers will have to be split further at a later stage (as my neighbors upgrade to fibers).

But wait. Why are there two fibers coming in a the box’ top-right corner, and another couple at the bottom right? This is supposed to be a patch-panel part, meaning all connections are internal!

The answer is simple: All four fiber subscriber installations were made with the fiber drawn directly from this connection box to the apartments. They simply ignored the connection boxes on each floor, and went directly down to the bottom floor. Why? Probably because the wiring infrastructure in this specific building makes it easier to draw a fiber all the way through, rather than to use the brain.

References

- Cisco has published a technical reference about GPON’s data transport.

- There’s a security analysis of an Alcatel-Lucent’s ONT, which shows a lot of what’s going on inside.

- List of ONTs that are approved by Bezeq.

- Quick explanation of the meaning of Nokia’s G-010G-Q LEDs.

Reader Comments

IBC/Unlimited doesn’t use PPPoE. They just seem to route the SLID directly to the assigned ISP maybe using VLANS or similar. Of course that requires the ISP contacting them for a provisioning change anytime you switch ISPs. This was similar when I had HOT cable modems for infrastructure and a different ISP.

I loved reading all the details of this blog, but am curious what you would do in my place. We have Partner & it’s been better than the Bezeq we had for years. Our cell phones are with Cellcom (we have NO tv), but find their service to ALWAYS SELL UP, which I HATE. So, we are about to get Fiber Cable for our house through Partner, but are told that it’s through Bezeq, who puts it up. I am just trying to figure out which Modem/Router to buy since I HATE paying monthly for the Partner router… Would LOVE to know which you recommend. We use many different computers & 2 cellphones. We do not GAME, but do loads of Streaming.

Stay Safe & healthy.

Here’s what I would do: First, ask Partner if they agree to an ONT that isn’t their. When I asked (a few months ago), I got a no. So that will probably finish up the issue.

I went for Cellcom, among others because they said they’re OK with me using my own ONT. But as I’ve written in the other posts that are linked above, they eventually forced me back to their. Which I don’t pay for, and yet, not the one I bought.

The ZTE F601 is a decent box, but it’s not a Wifi router. All in all, I suppose you will land on using what the ISP gives you.

Your details are great. Always nice. Thank you.

The link you gave to approved Bezeq ONTs (https://www.bezeq.co.il/media/PDF/gpon.pdf) is broken.

Our neighborhood just got fiber. So i’m thinking of “upgrading”. Right now we are using Bezeq-Bezeq. A year ago Partner was our ISP, then we moved, and i tried sticking with Partner… it did not work. And what a pain. In the old place i had used a dynamic dns, which worked. Then after we moved, apparently Partner was multiplexing multiple customers onto one external IP, and they (by necessity of the multiplexing) blocked *all* inbound ports. Of course they insisted they were not blocking any ports (liars). Eventually, Bezeq as the ISP would allow me to buy a dedicated IP for only 12 NIS extra per month. Annoying, but it opened up the ports and its working. So now we are Bezeq-Bezeq.

If i switch to fiber, i am going to want my same arrangement. Namely i want to be able to use dynamic dns with the ability to map incoming ports to specific internal addresses. Which means *I* want full control of port forwarding, something the last “Be” router i tried would not allow. Which is why i used Partner with my own TP-link dsl router – that they were, 4 years ago, happy to allow. And this time, Bezeq was also willing to also accept.

So an updated link to the list of ONTs that are allowed would be amazing, if you can find it. Thanks!

A bit late, however you are correct in assuming that the talk about “DHCP over fiber” is about having the router communicate with an ISP’s DHCP server, as with ISPs on Unlimited’s P2P fiber infrastructure before they were bought out by the group of providers headed by HOT, and with Partner on their P2P infrastructure (which, as it turns out, is also being slowly deprecated for GPON), and possibly also on Future Fiber’s infrastructure (not yet sure, I need to find time to purchase one of their router and SFP transceiver combos via the second hand market soon in order to verify this, also their infrastructure might also be P2P).

Also, to Mike, the link is not broken, you may simply have had issues with the connection at the time, or you may have tried opening the link just as the file was replaced with a newer revision, as this link, to this day, remains the same, with only the destination file being replaced with changes to the list (I have at least 6 revisions of it at this point, which I have saved on my desktop and my phone).

Hi, I have a Ubiquiti UXG-Pro with an SFP+ WAN port and was hoping you could recommend a GPON ONT SFP that will work with Bezeq fiber.

I live around Jerusalem.

I’ve noticed that all fiber optic service plans have asynchronous download and upload speeds:

300